Votive Mass of the Holy Spirit

for the Commencement of the New Legal Year

St Michan’s Church, Halston Street, Dublin

Monday, October 7, 2024

Homily of Bishop Paul Dempsey

ONE OF THE great mysteries theologians have engaged with over the centuries is the nature of the Blessed Trinity. Three persons, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, one God. Our Constitution opens with the invocation of the Most Holy Trinity. From a human perspective the concept and image of Father and Son are somewhat tangible, the Holy Spirit on the other hand, is a little more complex as the Spirit is not so corporal. Yet when we reflect upon the role of the Holy Spirit in Sacred Scripture, we discover the one we proclaim as the ‘giver of life’.

Today we offer the Votive Mass of the Holy Spirit as the new legal year commences. The Greek word ‘paraclete’ is often used of Jesus and the Spirit in the Gospel of John. Its primary, literal meaning is that of ‘advocate’ or ‘defender’ in a court of law. A role familiar to many here. With the passing of time, Christian tradition has tended to shift from the notion of Paraclete as ‘defender’ to that of ‘consoler’ or ‘comforter.’

We see the ‘consoler’ the ‘comforter’ in action in the Parable of the Good Samaritan we heard today. It is a story familiar to us all. We hear how a lawyer, to ‘disconcert’ Jesus, poses the question: ‘Who is my neighbour?’ In answer, Jesus shares the story we are so accustomed to. It has become part of our everyday vocabulary we categorise someone who has done a kind deed as a ‘Good Samaritan’.

To understand the full meaning of what Jesus is teaching we need to understand that the Jews and Samaritans were enemies, their divisions spanned centuries. The Jews viewed the Samaritans as a tainted, mixed race. The road between Jerusalem and Jericho, spanning about 17 kilometres, was known to be notoriously dangerous. The man in the Gospel learned this after being attacked and left for dead. The priest and Levite passed by. In Jewish law they were not allowed to touch a dead person, or they would be defiled. They kept the law but failed in the court of compassion. In contrast, the Samaritan, the one despised, transcends the division separating the two peoples over centuries. He sees a person in need and instead of ignoring him, reaches out to him. He recognises the dignity of the one before him.

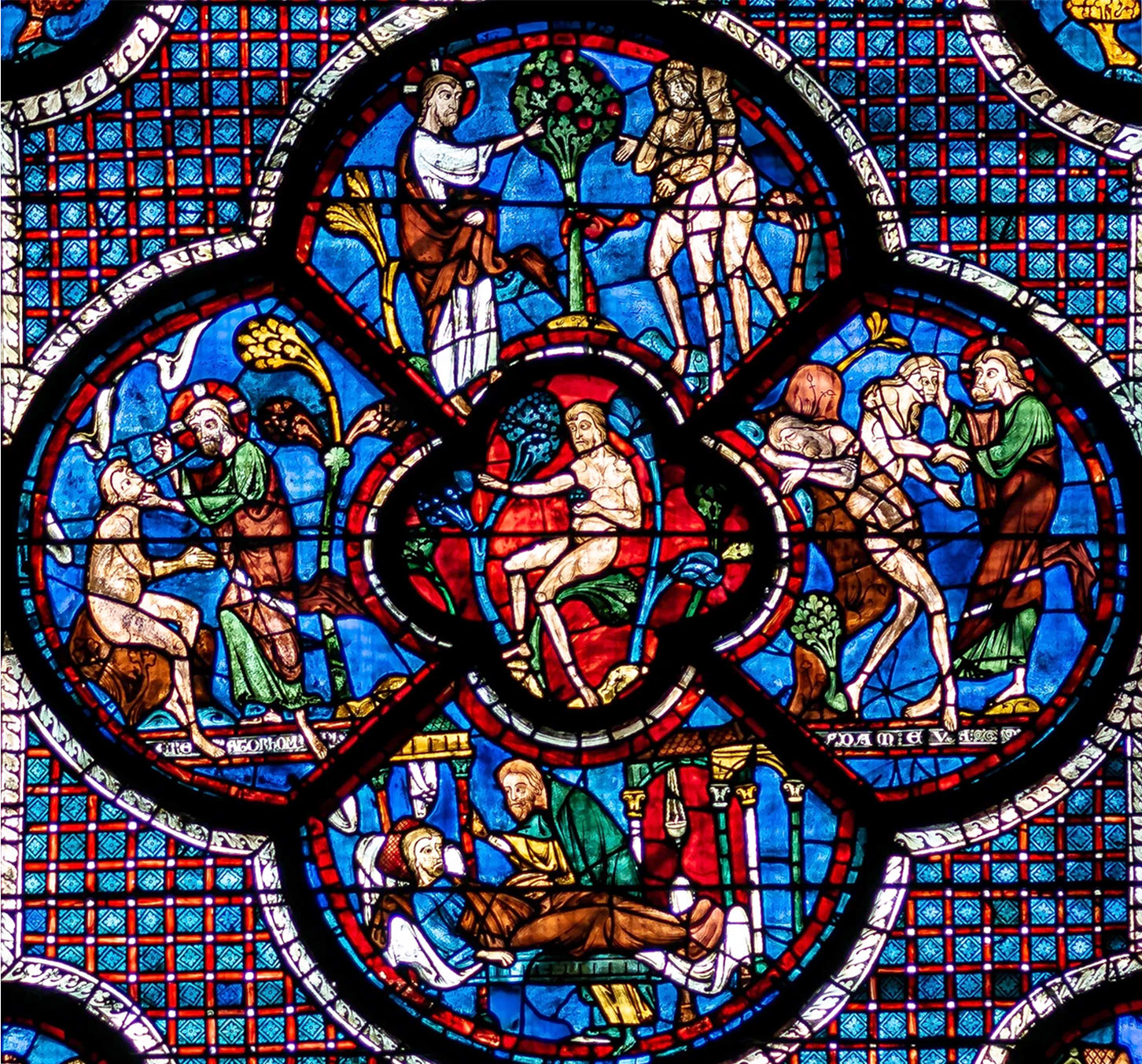

Important and all as this profound message is, there is greater depth in this parable that may not seem as evident when reading it for its obvious moral teaching. According to the early Church understanding, this story teaches more than a lesson about helping those in need. In the famous 12th-century cathedral in Chartres, France, one of its beautiful stained-glass windows depicts the story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden and below this, in the same window, is the image of the parable of the Good Samaritan; the narrative of the creation and fall of humanity is juxtaposed with that of the Good Samaritan. We might ask what the connection is between the two?

Many of the earliest Christian teachers saw Jesus himself as the Good Samaritan; the one who reaches down to a fallen humanity, wounded and suffering on account of brokenness and sin represented in the man attacked on the side of the road. Understanding the parable from this viewpoint adds an eternal perspective and value to its meaning. It takes it beyond the cliché, ‘Be a Good Samaritan’ rhetoric. This interpretation shifts the focus from us being the centre of the world to a humbler recognition that we are in need of salvation and healing ourselves. We move from being identified with the priest and the Levite who were solely concerned over their personal salvation, to being identified with the traveller, the broken one, who is in desperate need of help. This story is about us, we are the needy ones, who often find ourselves broken and wounded, and sometimes robbed of hope. But this is the very moment Jesus arrives, and unlike the Priest and Levite, he doesn’t ignore us, but reaches out to us, embraces us, carries us and heals our brokenness. He shelters us in his love, the place we find rest, where our wounds are tended to and healed.

We are in much need of this healing and hope today in our world and society. The brokenness and wounds of humanity are evident. Today, the 7th of October, marks the anniversary of the beginning of the war in the Holy Land. To date 41,000 people have been killed in Gaza. The situation in the region escalates daily. We remember our troops based in Lebanon and their families during these worrying days.

Closer to home, as we reflect upon the question in the Gospel, ‘Who is my neighbour?’ In our own country we are called upon to welcome people, who for various reasons, have come to find a home among us. The question is not only ‘Who is my neighbour?’ but ‘How do I act as a neighbour’? The Samaritan transcended the deep divisions in his culture and recognised the dignity of the other, enabling him to embrace him. The lessons in this are evident for those who fear others who are perceived as different from us.

The Church too has had to face and will continue to face its own brokenness. The pain inflicted on so many in past decades is a reminder that we mirrored the attitude of the priest and the Levite. We got lost in our own self-importance. Power and position became all too important, it obscured our call to be humble disciples, and as a result we failed to exercise the compassion and care expected of us. The wounds of this shameful chapter are open wounds and will always be part of our story and the story of survivors. Through all this the Church is called to return to its roots, which is the radical living of the Gospel, a Gospel which has much to say to our society today.

Bishop Dempsey with parish priest Fr Richard Hendrick OFMCap and the organisers of the Mass at Halston Street

Each one of you encounter the brokenness of humanity everyday of your professional lives. The complexity of human nature is indeed a great mystery. Each citizen is called upon to contribute to the common good and stands equal before the law. However, human nature is flawed and as a result, in your deliberations, you are called to find a balance between justice and mercy. A call that carries a heavy burden of responsibility.

In the face of these difficult realities, the parable of the ‘Good Samaritan’ opens new horizons, new possibilities for hope. Seamus Heaney told us that: “Hope is not optimism, which expects things to turn out well, but something rooted in the conviction that there is good worth working for.”

The late Pope Benedict broadens this when he paints the picture of the Good Samaritan for our contemplation, he tells us: “Jesus is the Son of God, the one who makes present the Father’s love, a love which is faithful, eternal and without boundaries. Jesus, filled with compassion, looks into the abyss of human suffering so as to pour out the oil of consolation and the wine of hope.”

As you begin this new year in this Votive Mass to the Holy Spirit, who is the ‘giver of life,’ may you know the conviction that, despite the complexities and tribulations of the human condition, there is good worth working for. Jesus, the Good Samaritan, out of compassion, reaches into the depths of a broken humanity to lift it up with his consolation and life-giving hope. May we as his disciples, respond to his call today to ‘go and do the same yourself’.