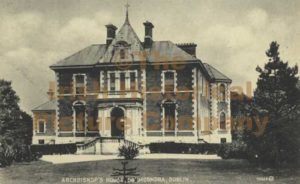

100 years ago this week and without the knowledge of the then Archbishop of Dublin, William Walsh, Éamon de Valera hid out in the gate lodge of Archbishop’s House in Drumcondra having just escaped from Lincoln Jail. The plot was carried out at the request of Michael Collins and Harry Boland assisted by Mgr. Michael Curran, then secretary to the Archbishop of Dublin.

The event is recorded by Eamon Duggan in the current edition of Ireland’s Own Magazine and with their kind permission we reproduce the article here

Ireland in 1919

The Witness Statements

The Recollections of Monsignor Curran

In my continuing examination of the Witness Statements in the Bureau of Military History I recently returned to the recollections of Monsignor Curran who was Secretary to the Archbishop of Dublin, Dr Walsh, from 1906 to 1919. Monsignor Curran kept a personal diary in which he recorded many fascinating insights in relation to the political scene in Ireland during that era. It seems that he had, in his capacity as secretary to the Archbishop, unrestricted access to many of the major political and church leaders across Ireland which allowed him to draw his own conclusions about the pressing issues of the day as well as the public figures involved in those issues.

Monsignor Curran opened his musings for 1919 with a commentary on the first meeting of Dail Eireann on January 21 of that year. It was, for all republicans and the country itself, a momentous occasion which generated a great deal of interest in Ireland but also beyond her shores. In his statement Curran recalled that there was much anxiety whether the meeting could be held in public at all and the fear was that the British and the Dublin Castle authorities might combine to supress it. The Monsignor noted that some sixty-nine pressmen were present in the Mansion House that day including many who came from abroad. All the proceedings in the chamber were conducted in the Irish language and Curran was very impressed by the manner in which the business was conducted and the decorum which was adhered to by all involved. Curran mentioned that no one was allowed to applaud during the meeting and he was struck by the undeniable fact that it signified the eclipse of the old political order in the country. There was no sign of the once powerful Irish Parliamentary Party and its six members who were elected chose, together with the Unionists, to attend at Westminster. Curran made the point that it had been so long since Irish Party members appeared in public in Ireland that the people had actually forgotten who they were. The 27 members who turned up that day were the Sinn Fein candidates who were not in jail or out of the country at that time like, de Valera, Collins and Boland.

While the political momentum was up and running there were still many republicans who could not participate in it because they were incarcerated in prisons not only in Ireland but in Britain as well. Curran mentioned in his statement that he had received a letter from Arthur Griffith who was in Gloucester Jail, expressing his thanks on behalf of his fellow prisoners to the Archbishop for securing Mass for them on Christmas Day. Curran also referred to the Inquiry set up to look into the treatment of Sinn Fein prisoners which opened on 28 January 1919 in Belfast and the refusal of the prisoners to take any part in it. The prisoners were represented by the newly elected TD, Eamonn Duggan, and he pointed out that their refusal to engage in the proceedings was based on the premise that the prison authorities and the Government had refused to guarantee that the facts, as given in evidence, would not be censored for publication and the refusal of the Government to produce all the necessary documents for the Inquiry.

In his statement Curran refers to the escape from Lincoln Jail of Eamon de Valera, Sean Milroy and John McGarry and he went on to recount how he took part in an elaborate scheme to hide de Valera from the authorities. He recalled that on Tuesday 18 February he received a telephone call from a Mr Keohane of Gill’s that Harry Boland wished to see him at their premises on the following morning. Curran duly met Boland that day and again two days later when they were joined by Michael Collins. Boland and Collins proposed that Curran should conceal de Valera in the Archbishop’s house. Curran admitted to being astonished by the suggestion but did get involved in the scheme. De Valera had at that time not arrived back in Dublin after his escape from jail and the thought was that the Archbishop’s house was the last place the authorities would expect him to take refuge in. Boland also pointed out that all the other usual places of refuge were either known to the authorities or under observation and there was also the attraction of de Valera being able to engage in physical exercise within the grounds of the property.

On Friday 21 February, both Boland and Collins turned up unannounced at the Archbishop’s house to inspect a place which Curran proposed should be used to hide de Valera. The first condition Curran laid down was that every possible precaution should be taken to safeguard the position of the Archbishop and that under no circumstances should he ever be told about the subterfuge. With that in mind Curran ruled out the Archbishop’s house itself but suggested that de Valera could be accommodated in one of the two lodges, one of which was located towards the Tolka end of the estate or the gate lodge located on the Drumcondra Road. The Tolka lodge was ruled out because it was too much under observation from a neighbouring cottage and so the decision was made to opt for the lodge on the Drumcondra Road which was occupied by the Archbishop’s valet, William Kelly and his family. The one fear Curran and his co conspirators had was that Kelly’s two young boys might give the game away even though they were unaware of who the visitor actually was. Boland and Collins were happy enough with the arrangement and they expected de Valera to arrive within the week.

Curran recalled that outside the Kelly family no one knew of de Valera’s imminent arrival with the exception of the Archbishop’s housekeeper, Ms Julia Corless, who had been consulted about the matter from the very beginning. As it happened the house itself welcomed many visitors at that time because meetings were being held there in relation the beatification of some Irish martyrs but Curran recalled not one of them realised the great Irish leader was so close by. Curran also recalled that he received a note from Boland on the afternoon of Monday 24 February advising that he should expect his guest, who was alluded to as “the parcel” that evening about ten o’clock which was later changed to eight o’clock. It seems that de Valera was coming from Dr Farnan’s house in Merrion Square which had been declared unsafe and he went from there to the sports buildings in Croke Park where he remained until the area between there and the Archbishop’s house was scouted and deemed safe to travel through.

De Valera left for the Archbishop’s house with Boland and a few minutes before eight o’clock Curran recalled he left the Archbishop’s dinner table and made his way to an unused gate which gave access to the eastern side of the estate. Soon de Valera and Boland arrived and Curran remembered they had a conversation during which they made arrangements for their next meeting. De Valera also asked Boland to procure a large size fountain pen for him which he could use on board the ship during his planned trip to America. With that, Curran escorted de Valera through the deserted grounds of the estate passing the brilliantly lit windows of Clonliffe College. During the walk de Valera recalled his own personal associations with the College.

De Valera occupied a room to the right of the entrance of the lodge which was fitted up as a bed-sitting room. Curran recalled that he spent most of his time revising “Ireland’s Claim to Independence” which he intended to be presented to the Peace Conference in Paris. Each evening after dinner Curran joined him for a walk in the grounds of the Archbishop’s house. He also arranged for Fr Tim Corcoran, a man who would later have a strong influence on W.T. Cosgrave’s Free State government, to visit de Valera during the evening of 28 February when they discussed the pending appeal to the Conference. De Valera also asked to see one or two other individuals including an old friend, Tom Morrissey, of the Records Office, who happened to be visiting the Archbishop one day on business. Curran also recalled a meeting of the Provisional government, chaired by de Valera, being held in the adjacent Dublin Whisky Distillers one day while he was staying in the lodge.

De Valera suddenly left around 3 March 1919 which surprised Curran who believed he would stay somewhat longer at the lodge. His stay was not detected by the authorities and he managed to carry out his duties and business with relative ease. As for the Archbishop, well he never knew the leader of Irish republicanism and the future leader of a free and independent Ireland had taken advantage of his hospitality. Though he takes no credit for his part in keeping de Valera safe from the authorities, Monsignor Curran’s willingness to participate in the subterfuge clearly marked him out as a man who wholeheartedly supported the prevailing view that Ireland’s future was set to be based on the principle of self-determination free from British interference and subjugation.